I jump around a bit in this one.

When I was 18 I fell in love with Jeanette Winterson as a character and as the writer of Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit. I admired the keen sense of irony she demonstrated in what she told her audience but also how she told it. Her fiction, which might have been (and probably still was) confused for her “facts of life” to nineteen, juxtaposed memoir with fairy tale tellings. These transitions felt easy even though, as she observes in "Deuteronomy" (“the last book of the law” in Oranges) that “People like to separate storytelling which is not fact from history which is fact. They do this so they know what to believe and what not to believe.” For Winterson, fairy tales, are no less reliable than historical accounts. Save for some generic conventions, history and “stories” are more or less the same in their truthiness; “stories” may even be more trustworthy because they suggest critical reflection by the reader. Though Winterson would rewrite the first five books of the Bible and make a character of the same name the protagonist, she is no omniscient narrator, and also shirks the epistemological authority that the historian would represent:

And when I look at a history book and think of the imaginative effort it has taken to squeeze this oozing world between two boards and typeset, I am astonished. Perhaps the event has an unassailable truth. God saw it. God knows. But I am not God. And so when someone tells me what they heard or saw, I believe them, and I also believe their friend who also saw, but not in the same way, and I can put these accounts together and I will not have a seamless wonder but a sandwich laced with mustard of my own.

I loved that her novel was something that queered history in clear and playful language. It became a go-to text for me because it made an argument for a postmodern ethic that wasn’t also hopelessly nihilistic. And I adored Jeanette for her sweetness, eccentricity, brilliance, and earnestness.

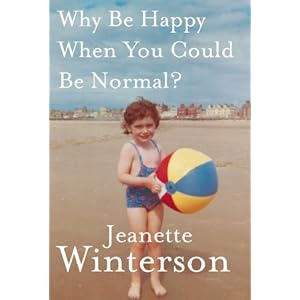

26 years after it was first published, Jeanette Winterson returns to Oranges in Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal?; she wrote the first when she was young, and wrote this most recent book when she was Junger. Funny that. I expect people fresh out of their English Lit degree to be in the midst of a love affair with psychoanalysis, but Winterson started later in life, beginning to study it in 1994 and more recently embracing a psychoanalyst as a romantic partner.

Winterson quotes Oranges and retells parts of it to, I suppose one could say, tell the history of her present: meeting her biological family, learning how to trust her most recent partner to love her, and her most recent experience of emotional devastation.

Curiously, she explicitly identifies that she will not discuss the period from about 1990 to 2007. I wonder what the rationale for that decision was. Was this out of respect for, for instance, the partners she had during these times? On the advice of her lawyers--to write only about people who signed releases / expand on a work published long ago... tested legal territory--to avoid lawsuits?

There are no fairy stories in this text, but there are allusions to Winterson’s perception of voices that are not be intelligible to others. In one sketch (she writes in sketches), she shares,

I often hear voices. I realise that drops me in the crazy category but I don’t much care. If you believe, as I do, that the mind want to heal itself, and that the psyche seeks coherence not disintegration, then it isn’t hard to conclude that the mind will manifest whatever is necessary to work on the job.

We now assume that people who hear voices do terrible things; murderers and psychopaths hear voices, and so do religious fanatics and suicide bombers. But in the past, voices were respectable—desired. The visionary and the prophet, the shaman and the wisewoman. And the poet, obviously. Hearing voices can be a good thing.

Going mad is the beginning of a process. It is not supposed to be the end result.

Ronnie Laing, the doctor and psychotherapist who became the trend 1960’s and 70s guru making madness fashionable, understood madness as a process that might lead somewhere. Mostly, though, it is so terrifying for the person inside it, as well as the people outside it, that the only route is drugs or a clinic.

And our madness-measure is always changing. Probably we are less tolerant of madness now than at any period in history. There is no place for it. Crucially, there is no time for it.

Going mad takes time. Getting sane takes time.

Here she is historicizing madness but she is not dismissing, discrediting, or devaluing the experience of madness, nor does she apologize for her own experience. And I love her for showing me an example of how this might be done.