I rather callously left Jane as she tried to find a hovel in the moors in which to sleep, so I should probably join her again. Before I do, however, I'll just note that the best part of reading Jane Eyre is still that I got to slouch up to the librarian like a prep' school rapper when I inquired, "In what area might I find the Fic BRO?"

I rather callously left Jane as she tried to find a hovel in the moors in which to sleep, so I should probably join her again. Before I do, however, I'll just note that the best part of reading Jane Eyre is still that I got to slouch up to the librarian like a prep' school rapper when I inquired, "In what area might I find the Fic BRO?"

Sunday, May 29, 2011

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Bronte

I rather callously left Jane as she tried to find a hovel in the moors in which to sleep, so I should probably join her again. Before I do, however, I'll just note that the best part of reading Jane Eyre is still that I got to slouch up to the librarian like a prep' school rapper when I inquired, "In what area might I find the Fic BRO?"

I rather callously left Jane as she tried to find a hovel in the moors in which to sleep, so I should probably join her again. Before I do, however, I'll just note that the best part of reading Jane Eyre is still that I got to slouch up to the librarian like a prep' school rapper when I inquired, "In what area might I find the Fic BRO?"

Thursday, May 26, 2011

Diseases of the Will: Alcohol and the Dilemmas of Freedom by Mariana Valverde

In this work, Valverde investigates how people and institutions have conceptualized the consumption of alcohol in the West. Specifically, she inquired about why the medical profession has not asserted ownership over the regulation of alcohol as it has with sexuality, and madness. Medicalizing the alcoholic, or the inebriate identity, was complicated by the popular and professional recognition of a link between habit and the one’s consumption of alcohol. Instead of confidently asserting that one’s drinking was due to a trait lodged within one’s constitution and thus within their purview, doctors did not represent a divided front with respect to drinking; they were divided about whether and to what extent one’s disposition to drink was (also?) a question of subjects’ routines and choices. Into the twentieth century, regulators and alcohologists of alcohol consumption have not resolved what it is that makes drinking problematic (even if their continued interest in it suggests that they consider it to have this potential), employing a number of different strategies that vary considerably by jurisdiction. A common element, she argues, seems to be that regulation black boxes how drinking alcohol leads to disorder and incivility; as if to tacitly affirm its ignorance of what it is about unruly drinkers that causes them to act disturbingly, governments impose regulations indirectly—limiting potential drinkers’ choices by dictating what shall [not] occur in certain spaces, but not criminalizing particular individuals’ actual consumption of alcohol.

Especially interesting was Valverde’s discussion of Alcoholics Anonymous, and how the ontology propounded by Bill W. and co. has become so salient. It reminded me vaguely of some of Agamben’s ideas. AA (et al.) would have it that everyone is the sovereign of their own kingdom, the hero of their own epic, the master of their own destiny. A.A. does recognize that an individual coexists with a higher power as well. This power does not really govern the individual, even if personal contentment and freedom require one to reconcile one’s purposes with this benevolent force (which can be done with a little work, with a little submission). At the same time, however, AA would have it that the “alcoholics” who it says should hold themselves accountable and responsible for their actions, who can remake their lives every day, will drown when influenced by the irresistible force of drink. It would seem that they are not so sovereign at all, but that the exceptional power exerted by alcohol makes it their ruler, compelling them to rearrange their lives so that they become out of synch. with their higher power or have to live their life “step by step”... thus, regardless of the salience of the aa argument, it is nevertheless confounded by the structure/agency problem.

Valverde notes the dominance of this model of the will, how it has been uncritically adopted by the recovery movement, and how at a cultural level its logic has become commonsense. While I was reading I was reminded of an example of a counter-discourse (from one of the few episodes I have watched of) Will and Grace.

Here Karen Walker characterizes A.A. mantras as “hate speech,” that the organization “goes against everything I believe to be good and pure in this world,” and that it is obliterating her support network. Here this outspoken non-alcoholic identifies people like her as a class that should be considered apart from A.A. but who are nevertheless minorities in danger of being assimilated by it. She, and people who are deemed like her by other characters of the show, might be worthy of study as an example of alternatives to the addict identity.

I have little to add to this summary right now, except maybe that I was impressed by the sensitivity that she wrote about AA. Valverde was very clear that her account was an exploratory one. She introduced the reader to this group, and in so doing highlighted the tremendous amount of comfort and support that it provided rather than rake it across the coals for the epistemological problems with its concept of free will. It was refreshing to read something like that, which instead of belittling things for being logically incoherent, acknowledged that recovery groups provide a function for which our current systems of thinking are not analytically developed enough to account.

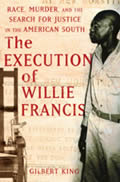

The Execution of Willie Francis

The Execution of Willie Francis, by Gilbert King, is a moving account that expounds on how discretion is written into law, and is protected by it, how deference to community standards may amount to following the rule of an imagined community, and the horrific realities of execution regardless of the wait or the means.

As King told the story, he frequently toggled between the story of Willie Francis and the history of the legal officials who shaped the last three years—a full sixth—of his short life. Through this sort of telling the author argued that the structure of Southern society made the execution of a black boy, who according to the record committed murder at the age of 15, inevitable. However, how King introduces some of these historical details rather abruptly, so that one moment the reader is focused on circumstances that immediately impacted Willie Francis’ welfare in 1948, and in the next moment the author has segued into a lengthy description of an execution that occurred over 50 years before. This leaves the impression of simultaneity, giving the sense that people are deluding themselves into thinking that the process of execution is any different in the time of Willie Francis than it was before. Indeed, it might involve more sophisticated technologies, but in the end it still was typified by the same racism, thuggish administration, and “imprecision” (read: painful, protracted deaths) as in the nineteenth century.

It was clearly written for a popular audience, and was a cross between true crime, history and a legal study. The chapters were short, and King structured them so that by the end of each chapter one was struck with a sense of all that was unresolved in a way that was evocative of a suspense novel. Gilbert King—a journalist—does not clearly, and systematically attribute each point to a particular source (possibly to make the text easier to read?). Nevertheless, his work contains rich historical detail, suggests an impressive survey of primary sources, and includes endnotes in which he records the sources that he consulted, and specifically notes where he drew quotations from. Though a transcript from Willie Francis’ trial was never made, he also demonstrated an interesting and impressive analysis of the minutes, and inferred therefrom that his counsel provided ineffective representation.

Nevertheless, I thought that the author might have better distinguished between the difference between legal proof and other standards of proof. Indeed, the author was wearing his barrister’s costume and poking holes in the prosecution’s case for the first two thirds of the book. When, in the last hundred pages, he shifted his perspective from one that doubted the culpability of Willie Francis in a homicide, to one that accepted Francis was responsible for the death of Andrew Thomas, it was disorienting. This shift might have been accomplished in more nuanced a way if the author bridged these two considerations with a discussion about the different kinds of homicide and culpability that attaches thereto, as well as the changing impression of sexual relationships between minors and men from the 1940’s to present day.

Additionally, King never really made explicit in his account that this was very much a story about white people, and about how white people perceive they treat black people. More particularly, it was written by a white non-Southerner about how he perceived white Southerners treated black people. How the author treats black people is at a remove. In terms of space in the text the white people in this story are definitely afforded the most, and the white and light-skinned heroes in this story are portrayed as morally exceptional. This is not just written into the subtext of the author’s lengthy descriptions of certain white characters acting for the black defendant despite the material consequences they might expect in a racist society. He also quotes a member of the NAACP who highlighted the significance of white allies’ sacrifices over those made by black activists. Having said this, this book does acknowledge the agency of racial minorities at this time, concluding the story with the image of a black boy instructing, and then comforting his tearful white lawyer.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)